By the end of Andrey Kurkov's "Good Angel of Death", a tale that took the reader through the Ukraine, over the Caspian Sea on-board a floating fish-processing plant, to the deserts of the Mangyshlak peninsula in Kazakhstan and back, a real affection for the Russian temperament, as personified by Kolya Sotnikov, the much-beleaguered main character, develops.

We're not even finished page one before there's a literary reference; to Tolstoy's "War and Peace", no less. I have found this to be an endearing characteristic of much of Russian fiction, and, in fact, it is via the references made in other writers' work that I discovered many of my favorite Russian authors, including Gogol and the much-beloved Pushkin.

And like Andrei Makine's, "Dreams of My Russian Summers", Kurkov's work is pervaded by a mystical sweetness that, although neither as comic nor explicit as Bulgakov's panoply of netherworld denizens who accompany "The Master and Margarita" on their berserk romp with the outrageous cigar-chomping cat, Behemoth, through a magically-imbued Moscow, Kurkov takes the reader on a gentle slide down sand dunes and over railroad tracks through some of the lands of the defunct Soviet Empire. (For Westerners, a map on the inside with the preface or foreword would be helpful).

But although it ensnares the protagonist in a skein of drug-dealers, arms smuggling and chemically-induced psychosis, it is remarkable for its lack of the testosterone-drenched machismo that makes the popular novels of the West so puerile and ultimately tiresome - more like junk food for the mind.

More like Ivan Goncharov's "Oblomov", Kolya Sotnikov doesn't drive events so much as they drive him, although to use the word "drive" in the same sentence as that epitome of laziness, Oblomov, is perhaps straining the point a bit. However, the passivity and acceptance with which Kolya leaves his apartment in Kiev to pursue a lost and buried artifact in the desert of Kazakhstan's Mangyshlak peninsula, demonstrates a passive acceptance of life's vicissitudes that would leave most US readers unsympathetic.

For whereas Vassily Aksyonov's character in "The Burn" exudes a begrudging affection for the West, while Roman Senchin's in "Minus", reflects a nostalgia for exactly what Aksyonov rejected about the Soviet Union, Kurkov's Kolya floats like a feather on the winds of change, constantly wetting his finger to see exactly which way they might be likely to take him next.

But as we follow him on his travels, and experience his travails, some of the rubes he hooks up with aren't so benign. Their attitudes sometimes frighten one with the somber notes they play. As though to illustrate what, in "The Future as History", Robert Heilbroner refers to as "... the conscious direction of aspirations away from material ends, toward glory, and faith ... that is, the employment of a fierce and often bellicose nationalism as compensation for the inevitable disappointments of the early stages of economic growth."

But, as Leopold Kohr's " Breakup of Nations" expostulates, the dangers of Nationalism are reduced with the size of the Entity encouraging it. No matter how fervid a Liechtensteinian's Nationalism, their power is so constrained by their complete dependence on neighbors, and its geographical footprint so diminutive, that its madness is contained and its self-love balanced by the need to attract foreign exchange.

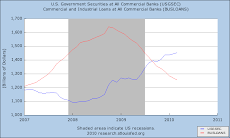

In much the same way, the Soviet monolith would have been much more dangerous had it had the rabid Patriotism and stony assurance of their exceptionalism that the US citizens cling to even as the West flagellates itself once more into an anguished ecstasy in preparation for yet another paroxysm of cataclysmic destruction.

Contrariwise, the easy way in which Kolya slides across one national border after another, smuggling (albeit unbeknownst to him) drugs, arms, and even a dead body for awhile, leaves one optimistic about the future in a way that tales of the Wild Child West simply do not. They more often leave one trembling for how The Requiem of a Dream will affect the US masses once they awaken from their torpor and denial.

Kurkov, like many of his countrymen, can still love his country, even while realizing that they are surrounded by fellow human beings who love theirs as well, with as true and good reasons as he does, without being made to feel terribly insecure by that fact. Such that, more than anything I've read for some time, it has left undisturbed my Kohr belief that Small is, indeed, more Beautiful. What a sweet book.

No comments:

Post a Comment